Photograph via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Clay is gripping the wheel for no reason. He fingers a Valium then puts it back in the bottle. Goes to the movies and stares at the green exit signs instead of the screen. Looks for his friend Julian in almost every scene of the book but when he finds him and their eyes lock nothing happens, Julian drifts off.

Listening to his friends talk, Clay wonders if he’s slept with the person being discussed. Waiting for someone at a Du-par’s diner in Studio City, he wonders if the gift-wrapped boxes in the Christmas display on the counter are empty.

Many of the people his friends talk about are indistinguishable to Clay. His own two younger sisters are indistinguishable to him, mere symptoms of the decline of Western Civilization, baby vipers who ask their mom to turn up “Teenage Enema Nurses in Bondage” by the band Killer Pussy, who put a pet-store fish in the jacuzzi to watch it die, who assure Clay they can get their own cocaine, and get mad when he won’t stop to look at the burning wreckage of a car accident near a McDonald’s in Palm Springs in the middle of the night. The McDonald’s, anyhow, is closed due to a power outage from wind.

Clay’s repeated phrase, which is also the author’s, spoken out loud on page one by Clay’s girlfriend Blair as she gets on the freeway, is that people are afraid to merge.

“People are afraid to merge.”

“What makes Iago evil? some people ask. I never ask.”

If someone hasn’t already mapped Bret’s borrowed use of a Didion device, to build narrative harmony and compression off repeating melodies, or of Bret’s echo of her boom-bust West and the thematic menace of rattlesnakes and mudslides and Santa Ana winds, someone eventually will. What are the psychodynamics of influence? some people ask. I never ask. Influence is a door that is opened. Didion opened it. He walked through, wearing her scarf and sunglasses. But as Clay tells Blair, who has given him a scarf for Christmas and wants him to try it on, “scarves usually fit all people.” One artist’s tricks in the hands of another, who understands how to use them, will produce something new.

***

Less than Zero was originally published in 1985. Like many other young people, I read it that year, at age sixteen or seventeen. Its author would have been twenty or twenty-one. I have a distinct memory that when I got to the end, I threw my copy out a window. The effect of this book on me required a drastic measure, apparently. I had never been to Los Angeles. I had never read a book by this author (no one had—it was, of course, his first). I was upset that he’d foisted on me this bleak world of rich kids in Wayfarers, playing Centipede or visiting an evil pimp in a penthouse, gaping at a dead body left in an alley for them to nudge. I still had some growing up to do, some toughening. Not in life, but in my reading, in my ability to see the value of art that hurts me. The year before, I had run out of the cinema in the middle of Blood Simple, by the Coen brothers. Literally fled up the aisle. But that movie and its sleazy ambiance touched me to the core.

What stayed with me from Less than Zero was Clay’s loneliness. He is eighteen and home on winter break from his first semester of college, and there’s this sense of returning to a realm he has vacated, as if he is forced to see his own life from a new remove, like a person visiting the world after dying. People keep telling him he’s pale, and they mean it literally—he’s been back east, in New Hampshire—but his complexion has another valence as well, that he’s a ghost, which is what allows him to see what the others cannot, to be affected by what leaves them so numb.

***

Rereading it now, Less than Zero is much more comedic than I’d originally understood. This is not a surprise, considering that American Psycho is so subversively funny, not overtly comic but with the deep shadows of a gag built into its core structure. Less than Zero similarly has a deadpan irony baked into most of the scenes. The boys all have these lopped-off and ridiculous WASP names—Derf, Rip, Trent, Spin, Spit, Finn, Chuck, and, of course, Clay. Those concerned that Clay needs a tan rely on a method that isn’t the sun or creams or even pills, but a process of being dyed in some kind of chemical bath. (Perhaps someday, if not today, the bizarre ubiquity of fake tan will seem as ridiculous as when Bret had merely made it up.)

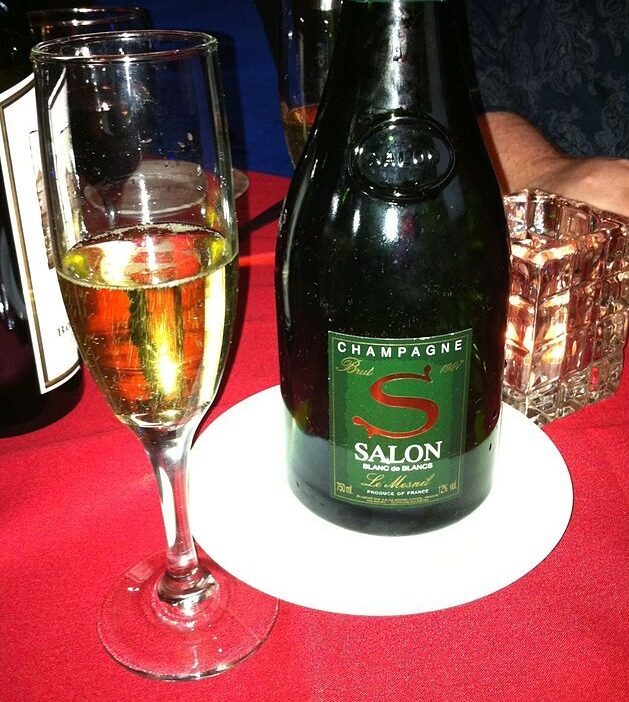

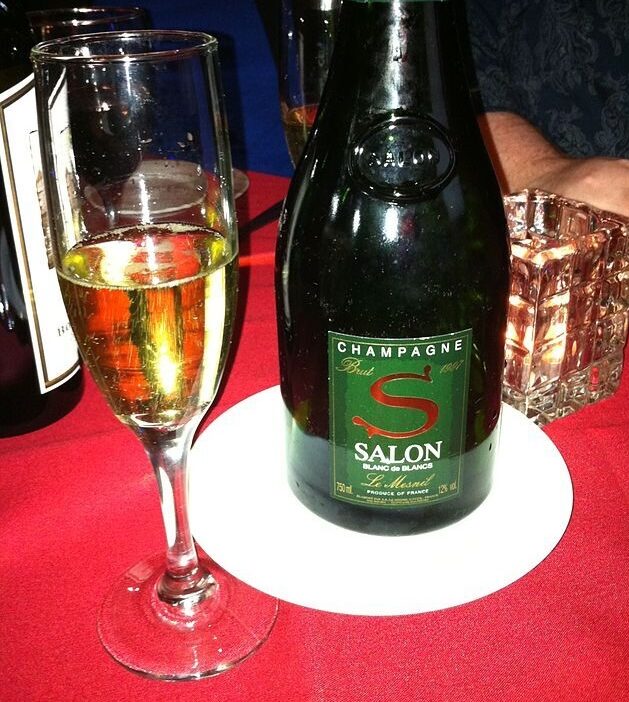

The characters are often drinking champagne, which has a tough job in this novel, a drink meant to bring a special occasion vibe, an adult refinement, to dead dynamics among the bored and the young and the restless. Characters say things like, “What does she know? She lives in Calabasas for God’s sake.” Clay’s friend Trent laments, “I’m just so sick of dealing with people,” and while it seems grave and right for someone in the book to say this, it’s also wonderfully funny. I’m just so sick of dealing with people. Me too, Trent, me too.

Trent comments that his mom feels sorry for their maid, whose family was killed in El Salvador, but that his mom will fire the maid anyhow. At an awkward gathering with Clay’s recently divorced parents, his mother gazes absentmindedly at the small Christmas tree that his father’s maid has decorated, a detail inlaid with just the right etching of acid. Rip goes into a rage in a video arcade when they won’t make change and he only has hundred-dollar bills.

There is casual destruction here and there, as dollops of mise-en-scène. Clay stares at a video of buildings being blown up in slow motion. A woman collapses on a sidewalk and no one seems to notice. A guy named Dimitri puts his hand through a glass window. “After taking him to some emergency room at some hospital,” Clay tells us, “we go to a coffee shop on Wilshire.” Trent tells Clay he had a dream where he saw the whole world melt.

Late in the book, as if exhibiting, finally, some tiny spark of life, Clay’s friend Alana says, “I think we’ve all lost some sort of feeling.” Just after, Rip comes to a similar conclusion. “I don’t have anything to lose,” he says mournfully.

The characters go to real places, like Ma Maison, and places that are not real but, on the fortieth anniversary of this novel, now, in 2025, are uncannily right, such as Trumps, a restaurant to which Clay’s father pilots his new Ferrari. Also now, in 2025, Trent’s nightmare has partly come true: whole swaths of Los Angeles have been incinerated, or washed away. There’s a feeling that we have now but not later, that beauty is fragile and fleeting, and that what happens to us is a portent of what’s to come for everyone. Dreaming that the world is melting has graduated from private concern, and metaphor, to here and now.

***

When I visited Los Angeles for the first time, in the late eighties, not too long after reading Less than Zero, it was June and the sky was leaden and gray, from its famous seasonal marine layer. The city was a foreign planet to me, with none of the provincial wholesomeness of Northern California. It was Mars. I was with college friends. We snuck onto the grounds of the Beverly Hills Hotel and went into an empty bungalow whose door was weirdly ajar, like someone had left in a hurry. It was maybe 4 A.M. and there was champagne in a bucket, still cold. Food on a dining service cart, also cold.

On that same trip, I was on Melrose, walking behind a woman in a super-short miniskirt with very tan legs and teased bleached hair and a red leather jacket. She had the exact look of the people in the videos I’d seen on MTV, people like Dale Bozzio and Kim Wilde. The woman’s legs were smooth and thin and the color of caramel. If you’re from Northern California, people don’t look like that. Their skin is not tanned to that color. The woman stopped walking and turned to enter a store, and I saw that she had the face of a very old person. It was a shocking revelation, on account of the illogical contrast of her legs and hair and leather jacket under the gray June light. Like I was Jack Nicholson in the moment in The Shining when the beautiful young woman transforms, in his embrace, to a corpse.

“I want to go back,” Clay’s friend Daniel says on one of their many aimless nights, as they have a drink at the Polo Lounge of the Beverly Hills Hotel. “Where?” Clay asks. There’s a long pause and Daniel, fingering the sunglasses he’s wearing in the dark bar, says, “I don’t know. Just back.”

Julian, a beautiful hustler lost in the undertow of his pimp, is Clay’s childhood friend. Clay holds on to memories of the two of them playing soccer in fifth grade. Likewise, Clay’s wonder at whether there’s anything in the boxes in the Du-par’s Christmas display is some atavistic grip on childhood. His friends would all know that the boxes are empty. What makes Clay worth caring about is that he’s not sure.

Indeed, a surprisingly traditional aspect of this debut novel is that it’s designed to give the reader empathy for Clay, Clay as the reader’s stand-in, who can witness the nihilism around him from a certain ethical remove. (By the time of American Psycho, Bret had dispensed with this convention, in the creation of a protagonist who requires a more sophisticated reader, one who can navigate moral ambiguity.) Even if Clay seems to his friends to be more or less like them—coked-up and disaffected—and even if he tells the reader that he wants “to see the worst,” poor Clay is somatizing all over the place. He’s nervous and breaking out into cold sweats, suffers insomnia and occasional crying jags. He’s easily thrown, with a fragile core of sentimentality, expressed in italicized sections of some other time, back when he could feel, reminiscences that connect Clay to his grandparents and a Western mythology of homey optimism, Clay as a boy on his grandmother’s lap, Clay hearing her hum “On the Sunny Side of the Street”—in other words, exactly the sort of narrative space that his friend Daniel longs to enter, in his vague desire to “go back.”

I daresay this entire novel is a somatization of Clay’s inner emotional reality. Like those frogs that secrete a hallucinogen that makes people trip, Clay has secreted the poisonous dream of this book so that we can see what he’s up against.

At the end, when he says he’s leaving, it’s such a relief. But Clay’s immersion in a world where nothing matters might already have wrecked him. He’s a ticking time bomb in the hands of his creator.

They all are. What Bret Easton Ellis had made, in this first youthful novel, was a cast that would return, in one form or another, under various guises, in other books. People who, like zombies, and because they are zombies, would be impossible to kill.

This essay will appear in the forthcoming reissue of Bret Easton Ellis’s Less Than Zero, which will be published by Vintage in May.

Rachel Kushner’s most recent novel is Creation Lake, a finalist for the 2024 Booker Prize. She lives in Los Angeles.